Pittsburgh’s Female Architects and Advocates: We ARE Women’s History

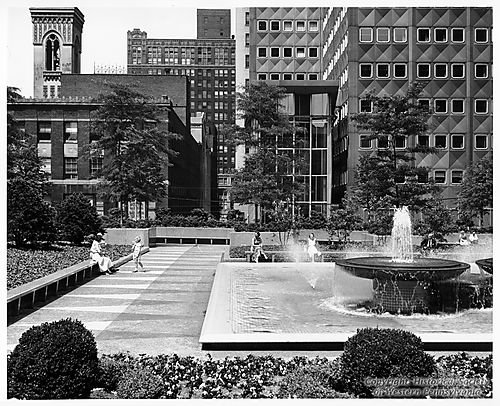

Shortly after its construction, three young women observe the plaque dedicating Mellon Square to its founders. Half a century later, women would be integral to its restoration. | Photo Courtesy of Susan M. Rademacher from Mellon Square: Discovering a Modern Masterpiece, p. 77

There’s an old adage that history is written by the victors, but I would argue that history is actually written by the storytellers, the advocates and promoters who craft the narratives about the victors. We don’t often think of the built environment as having winners and losers, though there are certainly people who win and lose when commissions are awarded, buildings are built, landscapes and neighborhoods are transformed. How the stories of the outcomes of these factors is told is as important as the outcomes themselves.

As Debbie Edwards writes in a previous Doors Open blog post, “it isn’t always easy to find traces of women’s history in downtown Pittsburgh.” This is largely not by accident. Historically, women were not invited to participate in the building (or rebuilding) of Pittsburgh in the same ways that men were. We know who ostensibly built the city – those oft-cited Captains of Industry: Carnegie, Mellon, Frick – because their names are constantly on the tips of our tongues. Their money may have fueled the building boom, but credit for the construction and advocacy for its preservation goes to countless thousands whose names we may never know.

Celebrating Women’s History Month is a challenge when we are not always certain to whom we owe a debt of gratitude.

In a recently published anthology, A Gift of Belief: Philanthropy and the Forging of Pittsburgh, editor Kathleen W. Buechel has assembled a complex cast to tell, and sometimes retell, the stories of Pittsburgh’s founding. One chapter by historian, scholar, and Director of the Women’s Institute at Chatham University, Jessie Ramey, tells of women’s contributions to the city through their philanthropic works. A highlight of the chapter is the revelation that Schenley Park, in Pittsburgh’s East End, is named for Mary Schenley, not her husband Edward. Though they shared a last name, it was Mary Schenley whose benevolence made the park possible. Often when we are referring to the built environment in Pittsburgh, it is stories such as Mary Schenley’s that highlight women’s contributions. Women were not, until recently, the designers and constructors of the spaces, but rather their advocates and supporters. Even when their names are on our lips, without knowing their full stories, their full histories, the import of their gifts are lost.

View of the Cathedral of Learning as seen across Panther Hollow Lake in Schenley Park, named for Mary Schenley

Women’s contributions to the built environment are no longer confined to just financial and vocal backing. A tour of the city reveals many of the most recent stand out projects’ teams have been envisioned, designed, and led by women.

The midcentury modern Mellon Square downtown with the Alcoa building rising beyond its central fountains.

Another notable civic space, Mellon Square, located across from the William Penn Hotel downtown, found its lead storyteller in Susan Rademacher, long-time Parks Curator for Pittsburgh Parks. Her book celebrating the history and revival of this park ensures that we know its truly remarkable history. The restoration effort in 2008 was led by two additional women: Patricia O’Donnell of Heritage Landscapes and Meg Cheever of the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy. It was through their advocacy and thoughtful intervention that Mellon Square, a midcentury modern gem of an urban park, has been preserved and restored for future generations of office workers to enjoy on a summer lunch break.

Mellon Square is adjacent to my current office space on the 25th floor of 525 William Penn Place. The building’s tenant lounge directly adjacent to the park, and the lobby of the building just beyond were both designed by teams led by and comprised almost solely of women. These compositions of glass and steel nod to the modern skyscrapers of downtown Pittsburgh’s heyday, but open up to the streetscape in a more contemporary and welcoming way. How few of us would have assumed that those enormous panes of glass, the soaring columns, and the retro futuristic supergraphics were designed largely by women? When such history goes unwritten, we lose the opportunity to know.

In their recent presentation of Transformative Place awards, ULI Pittsburgh recognized three teams for their contributions to the city’s urban spaces. Two of these teams were comprised primarily of women. The Roundhouse at Hazelwood Green and the interior courtyard at Pusadee’s Garden restaurant in Lawrenceville are significant additions to Pittsburgh’s built environment. They transform, each in their way, how Pittsburghers gather for work, for play, and for telling one another our stories.

The next time you dine at Pusadee’s (and you really should), make sure your dinner companions know the history of the space: that women were integral to its design and construction. Together, we can write the histories that will become our legacies.

The newly reopened Pusadee’s Garden restaurant in Lawrenceville boasts a luscious courtyard that transports the diner as surely as the food does. | Photo Credit Moss Architects

Lobby of 525 William Penn Place, renovated in 2020, led by a team of women from Perkins Eastman whose offices are now located in the building. | Photo Credit Perkins Eastman

The adaptive reuse of the Roundhouse at Hazelwood Green is one of the great successes of integrated landscape and architecture, led by Ann Chen of GBBN Architects. | Photo Credit Ed Massery