Hill District History Hidden in Former Nightclub Building

A modest building along DOORS OPEN Pittsburgh’s Fifth Avenue by the Numbers Guided Walking Tour route conceals an important chapter in the city’s entertainment history. For almost 50 years, the two-story commercial building at the corner of Fifth Avenue and Pride Street hosted musicians, politicians and sports figures. The Aurora Club, along with the Crawford Grill No. 2, the Hurricane, and other Hill nightspots, helped make music and Pittsburgh history.

The Hill District was Pittsburgh’s earliest and most diverse ethnic community. Eastern European Jews, Italians, Sicilians and Syrians crowded into the neighborhood’s tenements alongside Black migrants from the Deep South. These multi-ethnic groups shared some things in common: they all faced some sort of segregation and stigmatization. They struggled to find good jobs, housing, bank loans, and insurance. Adapting to anti-Black racism, anti-Semitism, anti-Catholicism and all of the other exclusionary practices prevalent in Pittsburgh and the United States, Hill District residents created their own economies, social safety nets and entertainment ecosystems.

The Hill’s rich cultural setting inspired pioneering Pittsburgh broadcaster Mary “Dee” Dudley to dub the intersection at its heart, Wylie Avenue and Fullerton Street, the “Crossroads of the World.”

Nightclubs, restaurants, hair salons, and barbershops did double duty. There were the public-facing business enterprises serving the newcomer communities. And then there were the off-the-books businesses. The informal (and illegal) street lottery called “numbers” was one of the city’s biggest twentieth century employers, with thousands working as runners and writers for Pittsburgh’s numbers bankers–people like familiar names like Gus Greenlee and Woogie Harris and lesser known folks such as Jakie Lerner and Frank Nathan.

Crawford Grill No. 2 | David Rotenstein

These entertainment entrepreneurs plied their trade in the backrooms, basements and upstairs apartments in buildings of the city’s most beloved cultural institutions such as the Crawford Grill and the Crystal Barbershop. The building at Fifth and Pride was no different. Built in the 1940s, it housed several businesses until 1963 when George Barron leased the second floor and opened his jazz joint, the Berryman and West Club. Named for a legendary 1930s jazz club once located above the Crawford Grill on Wylie Avenue, Barron changed its name to the Aurora Club in 1965.

Barron was a Pittsburgh native who got involved in the numbers in the 1940s. He made indelible contributions to Pittsburgh history as a numbers banker and as the owner of the Aurora Club. Some of the city’s top musicians played regular gigs there, including trombonist Harold Betters and drummer Roger Humphries. DJ Bill Powell hosted evening jazz sessions there. It was one of the clubs where local musicians and sophisticated fans knew there would always be good music. As an after-hours club, the Aurora attracted such sports figures as Steelers running back John “Frenchy” Fuqua.

The club’s role in Pittsburgh’s jazz history is well documented. But that’s only part of the building’s and Barron’s story. The two-story corner building concealed a lot of activities, however. During the day, Barron opened the second-story space to the community for political events and for parties for Hill District children. In 1972, for example, former vice-president and presidential candidate Hubert Humphrey held a campaign event in the club.

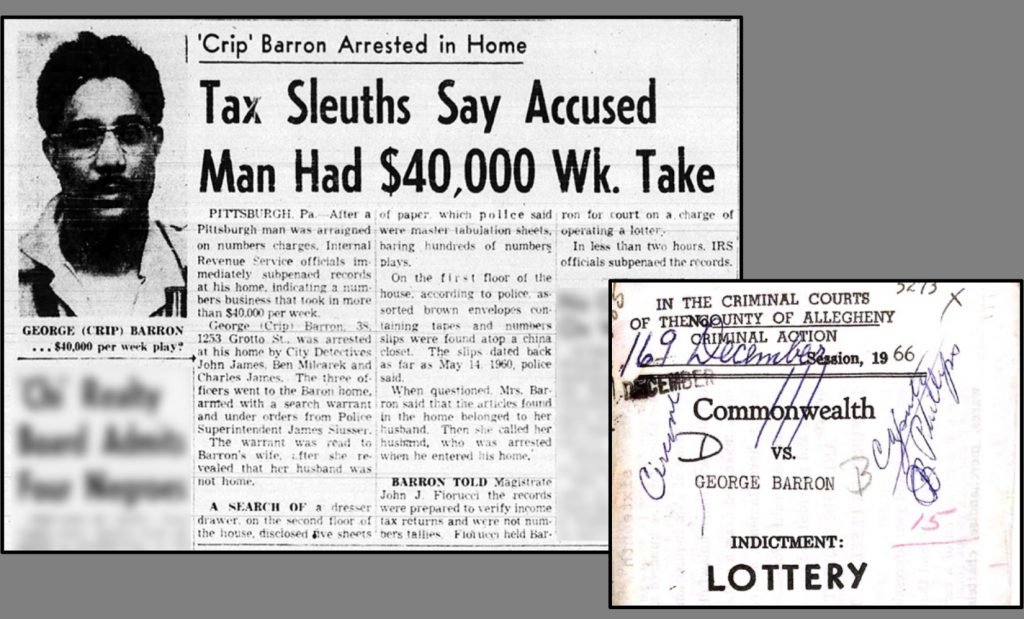

George Barron’s street name was “Crip” and Pittsburgh newspapers, documented his arrests, including this one from the Pittsburgh Courier, March 2, 1963. Also shown is a 1966 indictment for running a numbers racket (Allegheny County Court records).

Law enforcement officials and Uptown residents knew that racketeers, including Barron, counted daily numbers takes collected in the neighborhood in the club’s basement. For years, the first-floor restaurant housed Sugar’s Deli, an establishment that the Pennsylvania Crime Commission described as a place where a prominent local mob family collected and sorted bets. The building itself had been owned since 1950 by Antonio “Tony” Ripepi, a Mon Valley resident whom law enforcement officials and journalists described as the number three person in the region’s organized crime family.

Yet, for all of its entanglements with organized crime and racketeers, up until the 1990s the building had been a vital part of the community. When Barron died in 2001 at age 77, the Tribune-Review described him as a humanitarian. Like his Hill District predecessors Woogie Harris and Gus Greenlee, Barron returned a lot of the money he took in from the numbers racket to the community.

George Barron dancing inside the Aurora Club | Undated photo courtesy of Angela R. James.

Barron and his contemporaries occupied an esteemed position in Black culture: the badman folk hero. They were rule- and law-breakers but they also contributed to the local economy by employing many men and women as numbers runners and writers. After he died, Barron’s relatives talked about the times he opened the club to host parties for neighborhood children. As a member of St. Benedict the Moor Catholic Church, just a few blocks away from the club, Barron helped run bingo games and gave generously to the church. “Nobody escaped my father’s generosity,” daughter Trudy Thomas said in 2001.

Angela James, a retired Detroit police officer who grew up in Pittsburgh, recalled that she was about six or seven years old when she first visited the club. It was for one of Barron’s annual Halloween parties for neighborhood children. “The bar would have candy lined all the way down the bar and he had games and he had bobbing for apples and you got a bag and it had little trinkets in it,” she recalled in a 2020 interview.

Barron was like a father to James. “If you needed your rent paid, he was the person to see to help you. If you needed groceries,” she said. And the Aurora Club? “It was just more than a club. More than–for some people, it was probably a place of refuge, really.”

Former Aurora Club building in 2021 | David Rotenstein.

The club closed in 1999. Its clientele had changed in its final decade and the business had become a nuisance bar. After multiple violent episodes and many calls by neighbors to the police, then-Pittsburgh-Councilmember Sala Udin, a former Aurora Club patron and neighbor, successfully had it shut.

Though the club survives in memories and histories of Pittsburgh jazz, the building has been forgotten by historians and ignored by historic preservationists. A 2021 history of Pittsburgh jazz incorrectly stated that the club had been demolished during urban renewal. Historic preservation work for the Fifth Avenue Bus Rapid Transit line failed to recognize the 70-year-old building. Its façade, now an evolving canvas for graffiti taggers, conceals important stories about Pittsburgh and the people who helped make the Hill District the “Crossroads of the World.”

Author’s note on photo at the top of the page: Former Aurora Club building, c. 1990s | Photo courtesy of Angela R. James.