A Particular Inclination

Mark Houser explores inclines that set their cities apart with stirring scenic views

What do Pittsburgh, Paris, and Dubuque, Iowa, have in common? Okay, you could say they’re all river cities. But most cities are on rivers, after all. Hardly a uniquely identifying trait. It’s like saying all three cities have a museum, or that the people there really love coffee.

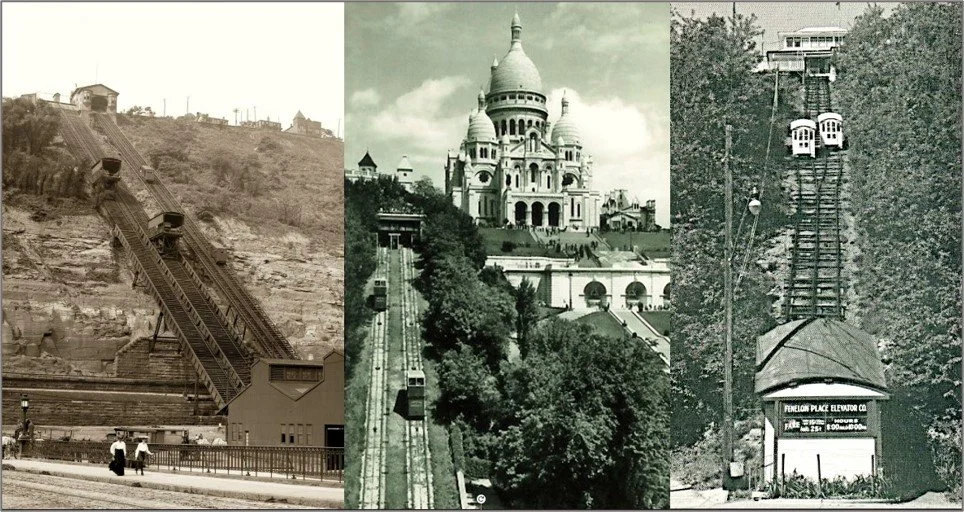

No, what these cities all have in common is historic passenger inclines. Each city has one — well, not to brag, but we have two—that’s been running for more than a century, and each boasts scenic views from the observation platform at their upper station. The one in Paris carries riders to the steps of Sacré-Cœur in Montmartre for romantic panoramas of the City of Light. The one in Dubuque offers stirring vistas of…well, Dubuque.

Pittsburgh, Paris and Dubuque Inclines

Pittsburgh is the home of the world’s oldest passenger incline in continuous service, the venerable Monongahela Incline, ascending and descending simultaneously since 1870. I wrote about it for the latest issue of Pittsburgh Magazine in “The Secrets of 10 Pittsburgh Landmarks” and found out some fascinating facts about the history of hillside transport.

For instance, another inclined railroad made it to the top of Mount Washington in 1869, the year before the Mon Incline opened, and it’s still going too. But this is a different, much bigger Mount Washington—the one in New Hampshire’s White Mountains, the most prominent peak east of the Rockies—and a different mode of transport as well. The world’s first cog railroad, its locomotives have a large central gear-shaped wheel that fits snugly into a holed track on the ground below (the technical term is a rack and pinion), enabling the engines to crank passenger cars up to the summit.

Vesuvius Funicular of song fame

The twinned counterbalancing cars of Pittsburgh, Paris, and Dubuque’s inclined railways are known as funiculars, a word derived from the Latin “funiculus” for the cord that connects them. It’s a mystery to my why we have chosen the dull, descriptive “incline” over the fun-to-say “funicular.” It’s even fun to sing. In 1880, a decade after the Mon Incline’s debut, a funicular began hauling tourists to the crater atop Mount Vesuvius, and locals wrote a novelty tune to celebrate its opening. In the Neapolitan dialect, they turned the word “funicular” into a verb: “Funiculì, Funiculà” means “Let’s Incline Up, Let’s Incline Down.” Their funicular was dismantled in the ‘50s, but the next time you ride up to Grandview Avenue, hum a few bars and imagine which of your favorite songs will still be recognized 141 years after its release.

The city of Naples still has four operating funiculars. Valparaiso, Chile, has more than a dozen. Pittsburgh’s two are the most of any U.S. city, though far fewer than the 15 that once climbed our hills. The concept of hauling things up a steep grade aided by a counterbalance had been around for centuries. In the 1830s, canal boats crossed the Allegheny Mountains near Altoona by being pulled up an inclined wooden track by steam engines and hemp ropes. Canal surveyor John Roebling, a German engineer who had come to Butler County to start his own farm, got his neighbors together to hand-wind ropes out of wire to replace the less reliable, less durable natural fibers. With the success of that enterprise, Roebling pioneered cable suspension bridges, including three he designed in Pittsburgh. None of them are standing today, but you can still walk or drive across Roebling’s grandest achievement, the Brooklyn Bridge.

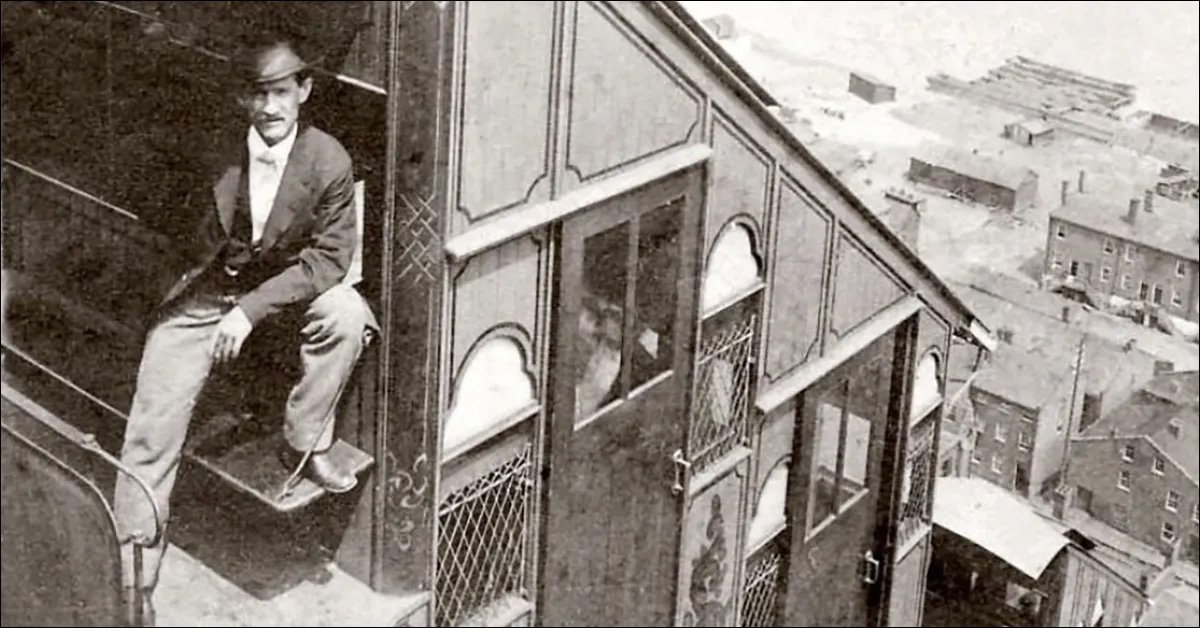

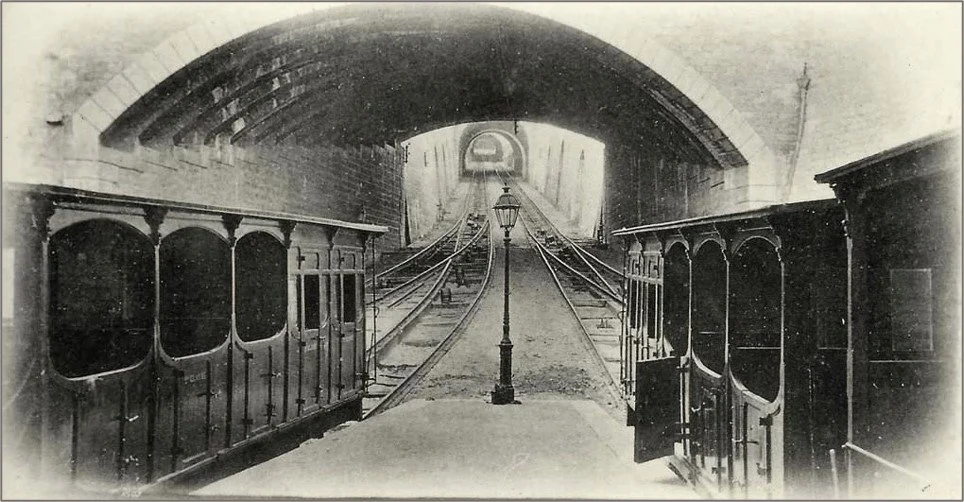

Lyon — First funicular or tunn-icular

And you can ride on the world’s oldest continually operating funicular, the Monongahela Incline. Its ungainly pale yellow triple-decker cars may not be as lovely as the iconic red trolleys of the Duquesne Incline, and the views not quite as Instagrammable. But they certainly surpass the views from the world’s first funicular. It opened in 1862 in Lyon, France, and its track went through a tunnel. At least we know to keep our inclines and tunnels separate.